Them Dems did better than expected Tuesday. Took the House by a comfortable margin. And while they’re still countin’, it looks like they’ll probably squeak through to take the Senate as well (51-49). As I suggested last post, this is fairly good news for online poker players . . . in theory. Still believe it is highly doubtful our new legislators are going to be introducing any changes to the UIGEA as it was passed at the last minute by the 109th Congress. Could happen, though. In theory.

Them Dems did better than expected Tuesday. Took the House by a comfortable margin. And while they’re still countin’, it looks like they’ll probably squeak through to take the Senate as well (51-49). As I suggested last post, this is fairly good news for online poker players . . . in theory. Still believe it is highly doubtful our new legislators are going to be introducing any changes to the UIGEA as it was passed at the last minute by the 109th Congress. Could happen, though. In theory.I also mentioned how electing new representatives and senators can’t really have much effect on how the UIGEA is going to be applied. That job is (mostly) now in the hands of the executive branch -- the U.S. Attorney General, those who serve on the Federal Reserve, and so forth. Those are the folks who are soon going to be telling banks, credit card companies, and third-party vendors to stop allowing us to transfer money to and from poker sites. I also mentioned how the “Civil remedies” part of the UIGEA gives district courts and state attorney generals the power to block ISPs. I should have pointed out that we do, in fact, get to elect our state attorney generals (in most states). So I suppose it is possible that our choices to fill those positions may have some effect on whether and/or how such “Civil remedies” are applied. (Not that there’s anything particularly “civil” about blocking access to poker sites.)

As long as we’re standing around theorizin’, I thought I’d share what I thought was an interesting theory about the fate of on online poker in America. This observation isn’t originally mine, actually. It was explained to me by my friend, Vera Valmore. Vera is one smart cookie. Among her many areas of expertise, she’s particularly versed in the areas of language and literature, as well as in theories connected with electronic media and communications. Though not a poker player herself, Vera has heard me gripe off and on lately about the UIGEA and so knows the general outline of the issue and the debates surrounding it.

The other night we were discussing the election and whether the recent legislation to inhibit online gambling would have any effect whatsoever. I told Vera about how when the Poker Players Alliance had tried to lobby Congress over the summer, they apparently had a number of representatives and senators who supported their efforts privately but who could not publicly come out against the anti-online gambling legislation. I was essentially paraphrasing something I had read a few weeks ago in a Two Plus Two post where a friend of a PPA lobbyist related how “even though many Reps, Sen[ator]s, and staffers played poker, it is still generally seen as a ‘sin,’ which made it extremely hard to get anyone overtly to support poker, its players, or the industry.”

“No surprise there,” said Vera. “I wouldn’t expect them to come out in favor of online poker.”

I agreed that poker has always been viewed in America as “sinful,” an activity associated with “outlaws” of various types. Indeed, poker has always been connected with the illicit, the illegitimate, the criminal. In Positively Fifth Street, Jim McManus recounts how poker has had a kind of outlaw status in America pretty much since the game first arrived in the early nineteenth century. As played on Mississippi riverboats, the pre-Civil War version of the game was routinely dominated by cheaters and thieves. “When they couldn’t beat you with marked cards, a ‘cold deck’ pre-sequenced to deal you second-best hand, or an ace up their sleeve,” writes McManus, such ruffians “pulled a pistol or switchblade and took your money that way.”

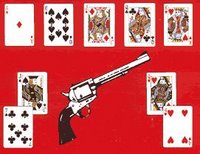

Such remained the case after the Civil War, with poker games continuing to be associated with the wild, wild west. Stories like that of the death of Will Bill Hickok -- sitting with his back to the door holding aces and eights -- became quickly established as part of poker’s lore. That the narrative of the modern age of poker is populated by figures like Benny Binion, Amarillo Slim, and Stu Unger -- legends, yes, but also figures of dubious moral character -- only reaffirmed poker’s notoriety in the public eye. McManus reminds us how the “frontier cachet” of poker continues even today, remarking how even those “cerebral advice” books published by Two Plus Two “feature a Colt .45, the gunslinger’s weapon of choice, on their covers.”

I told Vera how back in July -- shortly after the House passed H.R. 4411 -- the PPA had stated that “This bill would needlessly make outlaws of the millions of adult Americans who enjoy online poker.” And even though the version of the UIGEA that was passed doesn’t technically make it illegal to play online poker, it does indirectly reinforce the notion that doing so ain’t the sort of activity in which your average law-abiding citizen engages.

“You’re right,” I said. “Poker players will always be considered outlaws, that’s for certain.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about,” she interrupted. “Sure, there are always going to be those who see poker as a sin. But poker is still being played legally in . . . how many states . . . ?”

“Well, there’s some form of gambling allowed in every state except Hawaii and Utah,” I replied. “And all but a couple of those 48 states have casinos, where poker is certainly allowed. In fact, over half of the states permit what they call ‘social gambling’ as well, so it’s even okay to have home games in many places.”

“So poker is a sin but poker is America,” said Vera. “They aren’t going to make all poker illegal -- not ever.”

“True. So why can’t they publicly back online poker?”

Vera paused and shook her head, blinking slowly.

“Because it’s online. That’s why.”

I asked Vera to explain, and her answer was interesting enough I thought I’d save it for the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment